Many people have thought that there is an important connection between doing and learning; being active, or only passively involved in learning. Although quite a few are sure they understand it, actually the lack of agreement about the connection is evidence that none in fact have understood it. The best thing is to acknowledge all in one place, such as this page, some of the different connections between doing and learning that are well-established, and not fall into the belief that there is only one thing to know here.

Firstly, one connection that will not be focussed on here, because it is of a different kind than the rest: in education, constructivism in its simplest and most widely acknowledged form points out that we have never been, are not now, and have no (as yet) forseeable prospect of being able to insert knowledge into someone's head as we can insert a computer memory stick into a computer's USB port. Instead, a real activity has to be performed by the learner which no-one else can do for them: knitting the new ideas into their pre-existing web of information and ideas. This is an action; it is effortful and time-consuming, and is probably never completely accomplished. No doubt that it is learning; nor any doubt that it is "doing" in an important sense. In education it is similar to the concept of deep, as opposed to surface, learning. We should remember this; but no more will be said about it here other than to remember that the words "doing", "learning", and "activity / active" apply to it, although in a different way than other connections.

The pervasive false attribution of the idea that activity is vitally important for learning

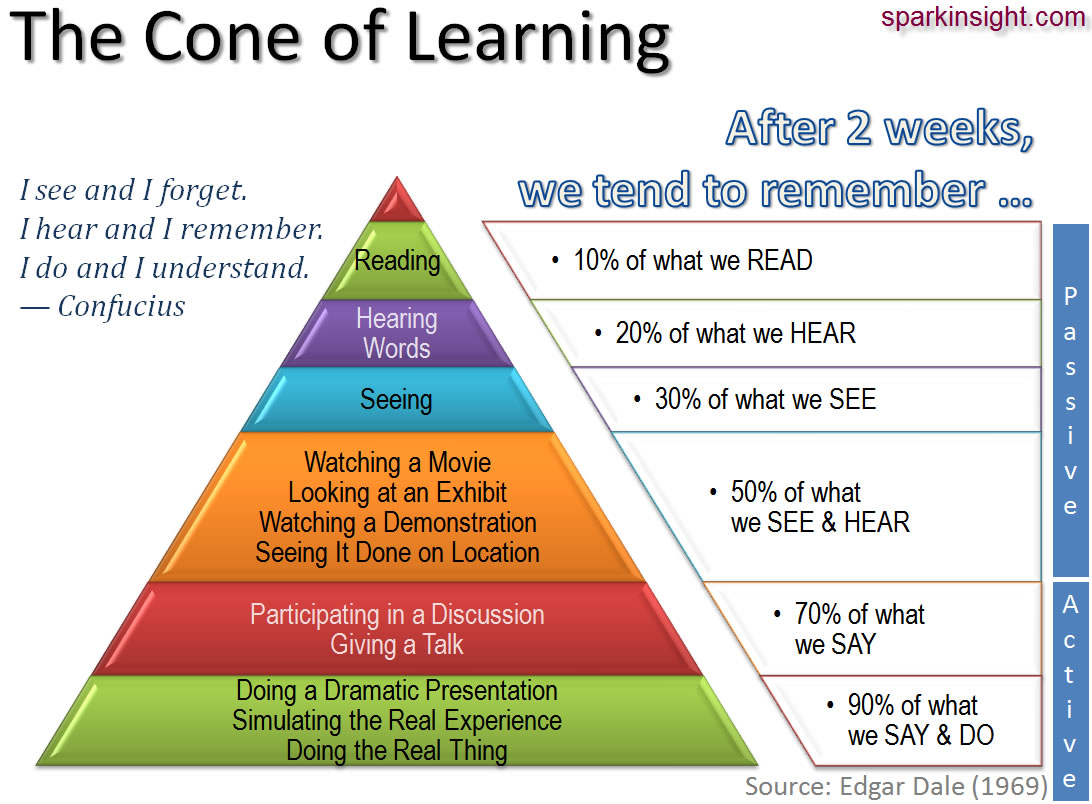

So widely believed in recent times is the notion that learning is greatly enhanced by the learner visibly doing something that slogans expressing this have been widely circulated, uncritically acclaimed, but falsely attributed to lend them a credence they do not merit.

The highlights are:

- The "quotation" is "I see and I forget. I hear and I remember. I do and I understand." or sometimes "Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn."

- It has been variously attributed to: Aristotle; Confucius; Benjamin Franklin; a Native American proverb; a Chinese proverb; Voltaire; the Association For Experiential Education.

- First published in 1986 AD

- But often attributed to as long ago as 500 BC

- Illumination came in 2012 from

Dakin Burdick who showed that:

- It does not come from Confucius.

- It might be a loose rewriting of something by Xun-zi a.k.a. Hsüntze (313 BC - 238 BC).

- In which case the translation could be: "Ignorance is worse than hearing it, which is worse than seeing it, which is worse than understanding it, which is worse than doing it."

- (But these might be the words of someone arguing that training is more important than education i.e. someone who thinks that doing is the ultimate aim and end of learning, not the start of it.)

A fuller account of this delusion, or fraud, is here.

The surgeon's mantra; and Bacon's triad

"See one, do one, teach one".That is a mantra that surgeons have, and in fact adhere to very widely. It is a cliché, sounds glib, yet contains more educational wisdom than most academics apply to their own courses. It is actually rather deep educationally when it comes to learning skills (as opposed to declarative knowledge). It downplays the reading about the procedure, and the explanation and evidence contained in the reading. But it identifies the separate learning of first the perceptual aspect, then the motor aspect, and finally the overall (metacognitive?) aspect, including being able to talk about it to other people i.e. in terms of public shared concepts. More on this here.

"Reading maketh a full man, conference a ready man, and writing an exact man."

This mantra too contains educational wisdom, and applies to many more HE disciplines than surgery, but makes clear that not one but three activities (reading, discussing, and writing) are important and contribute different things to good learning, at least in HE i.e. you cannot just pick the activity that is most convenient but need all three. This is a 400 year old insight that comes from a 1625 essay by Francis Bacon. More on this here.

The key idea in both these mantras is that there is no preferred order of merit in the activities, but on the contrary, that a fully successful learner must do all three: this is the opposite than what was asserted in the fictional proverbs of the previous section, where differences in the dominant sensory modality were seen as differences in effectiveness rather than the insight that all must be learned because all are essential aspects of the topic.

Chi's framework

A much better substantiated view (founded on many published experimental studies) is Chi's passive-active-constructive-interactive framework: The idea is that the four are in ascending order of mathemagenic power:- (Inactive e.g. not paying attention)

- Passive e.g. reading

- Active e.g. answering a closed question

- Constructive e.g. generating reasons or "self-explanations"

- Interactive (with peers).

Note that Chi's "passive" level is reading: and that that is definitely an active, indeed physical and bodily, process too.

The key sense of "active" in Chi's work, is how much mental work is done by the learner, in generating answers that are not "there" in the materials and other prompts give to the learner. But Chi has established not only that doing or activity are important to learning, but that different kinds of activity have definite and repeatably different amounts of benefit in terms of how much is learned.

Chi,M.T.H. (2009) "Active-constructive-interactive: A conceptual framework for differentiating learning activities" Topics in Cognitive Science vol.1 no.1 pp.73-105

Fonseca,B.A. & Chi,M.T.H. (2011) "Instruction based on self-explanation" ch.15 pp.296-321 in R.E.Mayer & P.A.Alexander (eds.) Handbook of research on learning and instruction (New York: Routledge).

Summary

- Hidden and inescapable activity:

Learning in humans is itself an activity: the hidden weaving of new

information and ideas into what the person already knows. It is a hidden

mental activity. It is not an activity in the sense of one

organised by the teacher and which might be omitted by a different

teacher. Above all, it is not an optional physical activity which is

what constitutes "doing": an activity in the sense of the activism

concept in learning.

It might be called "processing" or "integration" or "digestion".

Having said that, we should not underestimate the amount of passive accumulation we do; not the importance this eventually has for coming across things we did not intend to learn at the time, but eventually realise we need to attend to.

- Indiscriminate adoption of activities: A general crude belief that action by learners is always and unconditionally good for learning is very widespread. (But what is needed is understanding of what kinds of activity are helpful, and in what conditions.)

- A particular set of activities: Two old and respected rules have in common that three activities are important, but are not interchangeable: better learning depends on engaging in all three. I.e. not any activity, not one activity, but particular sets of them.

- Rank ordering of alternative activities: Chi's framework, in contrast, offers a classification of four types of activity, and shows that these types or groups of activity can be ranked in order of effectiveness at promoting learning. So activities are not equal in merit. Her best class, "Interactive", means having two learners following a worksheet (to keep them on topic) and discussing questions of issues on the worksheet. Peer discussion has been widely shown to involve each learner generating reasons (Chi's next best category), and also reading. In other words, her better categories also involve the lower ones.

- Possible integrations of these ideas:

We might reconcile Chi's conclusions with the "particular sets" rules by

either:

- Thinking that one must first identify the essential set; and then for each member of that set, identify the hierarchy of alternative forms of that member and picking the best form of that activity.

- Noting that the sets could be seen as each using different stimuli whose power to stimulate learning differs from each other, so that using all three to some extent gives additive power.

My old plan for this page, now abandoned

Doing and learning: activism Laurillard principles (public/private) My MinMan chapter Primary schools and busy work What kind of activity? mental? varied? ... Chemistry: not 2 but 3 kinds of alternative representations here? So what is the deep principle here? a) Deep learning and multiple types of link? b) Specially public/private concept names <-> personal perceptual stuff c) Mental (re)processing: not just one task but several Deeper view: LBE vs. narrative

Web site logical path:

[www.psy.gla.ac.uk]

[~steve]

[best]

[this page]

[Top of this page]